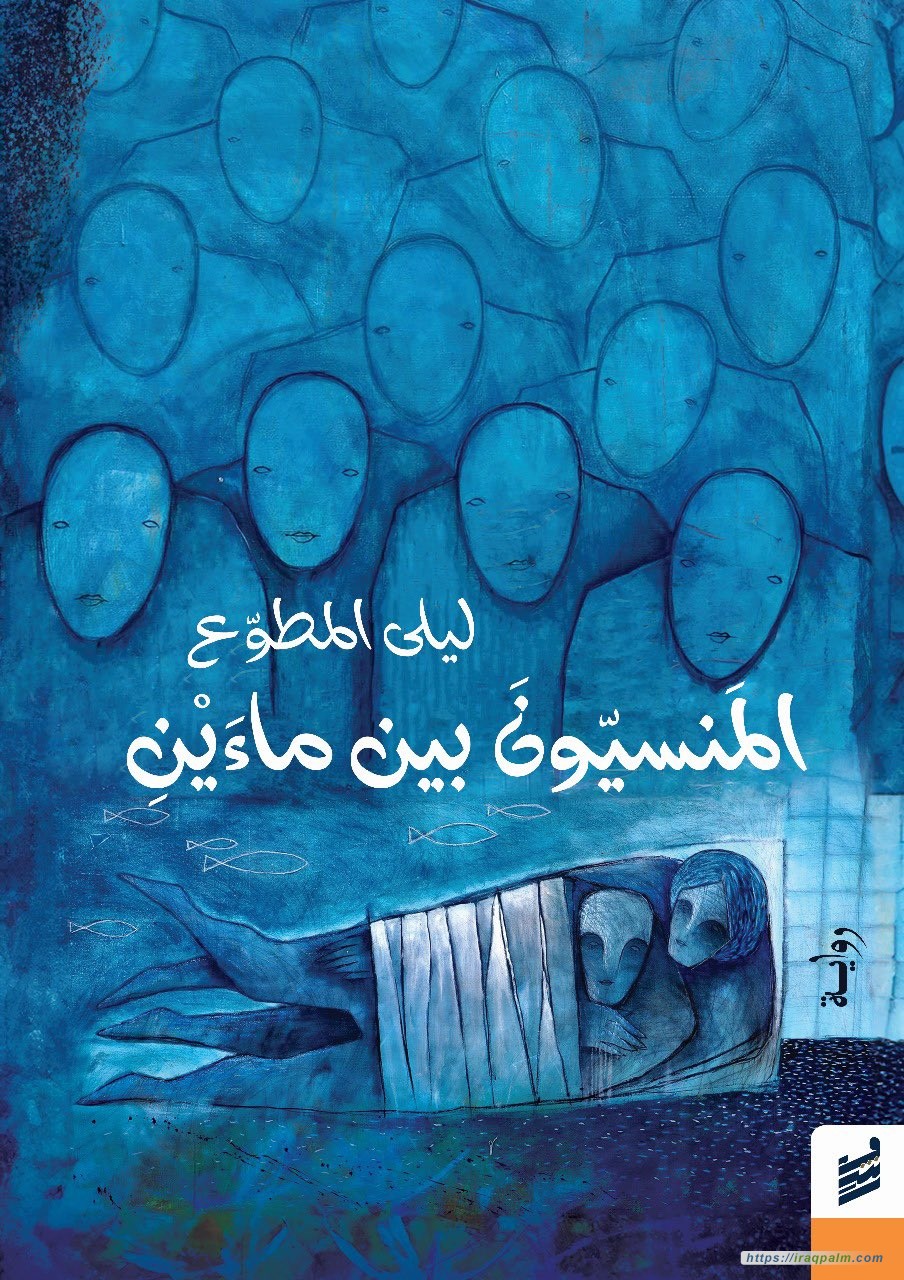

ليلى المطوع تسرد تاريخاً غرائبياً بين الماء والصحراء- بقلم الناقد محمد السيد إسماعيل -The Forgotten Between Two Waters : A Novel of Imagined Life in a Maritime World

المنسيون بين ماءين رواية الحياة المتخيلة في عالم البحر

ليلى المطوع تسرد تاريخاً غرائبياً بين الماء والصحراء

بقلم الناقد والشاعر محمد السيد إسماعيل

نشرت في صحيفة اندبندنت عربية

تاريخ

٢ يوليو ٢٠٢٤

على رغم كون الكاتبة البحرينية ليلى المطوع ناشطة نسوية ومدافعة عن حقوق المرأة، فإن روايتها "المنسيون بين ماءين" تتجاوز حدود القضايا النسوية. فهي في جانب منها تستعرض تاريخ سكان إحدى الجزر في أسلوب يتسم بالأسطورية، مع وجود إشارات اجتماعية مهمة حول وضعية المرأة التي مثلتها نماذج نسائية عديدة."

تعتني الروائية البحرينية ليلى المطوع في روايتها الجديدة "المنسيون بين ماءين" (دار رشم) بدلالة "الماءين" الواردين في العنوان: ماء البحر، وماء الينابيع الواقعة فيه. ومن هنا جاء اسم "البحرين" الذي يطلق على هذه المنطقة الجغرافية. إن الماء دال محوري، فالكاتبة، كما تصف نفسها، هي "ابنة الماء"، أو ابنة جزيرة ويشكل البحر جزءاً من هويتها. ولم تبالغ المطوع حين قالت في أحد العناوين الفرعية: "إنا من الماء وإنا إليه لعائدون". وهو ما يتوافق مع ما ورد في القرآن الكريم: "وجعلنا من الماء كل شيء حي". إن ما سبق يعكس خصوصية هذا المكان المحلي في ماضيه وحاضره. ولعل أهم خصوصياته معجزة وجود ينابيع مياه عذبة وسط أعماق البحر المالح، وتوظيفه أهم الأساطير المنتشرة في هذه المنطقة. ومنها أسطورة غلغامش الذي رحل إلى هذا المكان بحثاً عن عشبة الخلود، والأسطورة الفينيقية التي تدور حول المرأة التي لا يعيش لها وليد، ولا يخرجها من هذه اللعنة إلا وطء دم شريف. وهو ما حدث مع "سليمة"، حين وطأت دم "طرفة"، بعد قتاله مع رسول الوالي.

طرفة بن العبد

مرت سيرة طرفة رغم نهايتها المأسوية مرور الكرام في المراجع القديمة لكنها عولجت معالجات كثيرة في البحرين، كان أبرزها السيرة التي كتبها الشاعر قاسم حداد. غير أن إشارة طرفة في أحد الأبيات إلى النساء "المقاليت" اللائي لا يعيش لهن ولد أوحت للكاتبة فكرة هذه الرواية. فاخترعت شخصية "سليمة" التي انتهزت الفرصة ووطأت دم "طرفة"، ومن هنا اشتعلت نار الانتقام داخل شقيقته "الخرنق". وكان ما فعلته "سليمة" على غير هوى زوجها "صفوان" الذي نبهها إلى أن "الخرنق"، "لا تأكل إلا لحم الجمال، تأخذ من حقدها وذاكرتها الكارهة لمن أساء إليها". لكن "الخرنق" لم تلجأ إلى القوة والمواجهة المباشرة، بل إلى الحيلة، فانتظرت مرور الوالي لتنشد أشعاراً في جمال امرأة حسنة القد شهلاء مكتنزة مشتهاة. تجاهل الوالي ذلك أول مرة، ومع تكرار الموقف يسأل الوالي من معه عن هذه المرأة الجميلة فلم يجدوا إليها سبيلاً، فتشب فيه نار الولع ويستدعي "الخرنق" ويسألها فترد بابتسامة ماكرة: "إنها سليمة زوجة صفوان". فطلب الوالي من خادمه أن يطلب من صفوان إكرامه بجسد "سليمة". ولم يخرج الزوجان من هذا المأزق إلا بإرسال امرأة جميلة إلى الوالي. وحين علمت "الخرنق" بذلك انتظرت مرور الوالي ووصفته بالمخدوع، وعندما تأكد من ذلك أمر بقتل "صفوان" وصلبه. وهنا تهرب "سليمة" وهي حبلى إلى الضفة الأخرى، والعجيب أنها تضع وليدها داخل البحر ثم تخرج به إلى الشاطئ.

تعدد الرواة

الرواية مسرودة بصورة رئيسة على لسان "ناديا" (المعاصرة) لكن ذلك لم يمنع تعدد الأصوات السردية، ما بين ضمير الغائب وضمير المتكلم في الفصل الذي يحمل عنوان "ما حدث لناديا" التي تقول: "أدور على نفسي، إنها الشمس فوقي تحرقني، تؤذي عيني. هذا المكان الذي عبرته سليمة، كما ذكر في الواقعة. ولكن أين البحر؟ أين زرقة الماء وتلونه؟". إن السؤالين الواردين في نهاية الشاهد، هما علامة على تحولات المكان، سواء بفعل البحر نفسه أو بفعل البشر. إننا أمام تقابلات تزخر بها الرواية، منها ثنائية الماضي الذي يعود إلى آلاف السنين وتمثله شخصيات مثل "طرفة" و"سليمة" وأمها "بثينة" وزوجها "صفوان"، و"الخرنق"، والحاضر الذي تمثله "ناديا" وجدتها "نجوى" وأستاذها "آدم". والحقيقة أن هذه الثنائية تكاملية، فالحاضر يستدعي أحداث الماضي بغرض إسقاطها على ما هو معاصر، وليس فقط لتأكيد الهوية. فالمقابلة الأخرى الحدية التي تقوم على الصراع تتمثل بين البحر والصحراء أو الماء واليابسة، ثم المقابلة التكاملية بين الأساطير والواقع، والعذوبة والملوحة الممثلتين في الينابيع والبحر. يقول "آدم": "هذه الينابيع كانت من أسباب نقاء اللؤلؤ، ماء عذب في وسط البحر المالح ومنه كان أجدادنا الغواصون يتزودون بالماء في أثناء رحلات الغوص"، مما يجعل من هذه المقابلة ثنائية تكاملية. على عكس ثنائية الماء واليابسة، إذ نلاحظ أن غالب الينابيع قد "جفت بسبب عمليات الردم والبناء وإنشاء الجزر الصناعية وتوسعة الأراضي". وهو ما يجلب الخديعة حين نرى في الصحراء سراب الماء، وفي البحر سراب اليابسة. إضافة إلى ذلك هناك ما يسمى دراما القتال بين "طرفة" والمرتزق الذي أرسله الوالي والذي قال للأول بصوت عال وهو يدور ليصل الصوت إلى من اجتمع ليشهد النزال: "اختر طريقة موتك، فإني قاتلك لا محالة". لكن "طرفة" يأبى ذلك بغروره المعروف، فهو يعرف أنه من قبيلة الأشراف الذين لم تجز لهم نواص أو تسب نساء، ويشرعون صدورهم للموت ولا ينحنون أمام ملك ولا يخشون مرتزقاً، لكنه يموت ميتة قاسية.

رة منها بالتفكير الأسطوري. فالأسطورة هي حياة هؤلاء البشر وقرينة وجودهم وموجهة خطاهم. فسليمة تشعر بالقبضة التي لمستها، وتجد أن الماء قد ترك على جلدها أثراً ليد صغيرة. إنها يد ابنتها "أميمة" الأضحية التي "تلاشى جسدها مع سيلان الماء منذ أعوام". وقبل اجتيازها للبحر حذروها أن تمتد يدها إلى أي فاكهة وذلك لأن البحر سيعلم، "وسيطالب بها، وسيقلب القارب". وهذا يذكرنا بما اقترفه كل من آدم وحواء حين أكلا من الشجرة المحرمة وكان ذلك سبب طردهما من الجنة. كما يذكرنا بامرأة لوط التي تحولت إلى عمود ملح بمجرد نظرها إلى الوراء، إذ يسمع صفوان "صوت النسوة المتوجعات وهن يسرن مبتعدات عن البقعة المقدسة، قاومن، فلا يلتفتن إلى الوراء". وهناك التضحية بالبنات الأبكار على نحو ما يقال عن العادة في مصر القديمة، فقد كان هناك من ضحوا ببناتهم أمام الآبار ومعهم أشراف القوم من كل قبيلة، حتى تبشرهم الكاهنة الكبرى بالماء حتى سمعوا خريره فهللوا فرحاً. وتتوازى مع هذه الحادثة ولادة الحياة من الموت، وهذا ما فعلته سليمة مع طرفة لترزق بالوليد. وهناك ما يسمى أساطير الطبيعة حيث يروى أن "الدبران" كان رجلاً فقيراً، "أحب ثريا الفاتنة فمنحها أغنامه لكنها رفضته. أخذ يتبعها مهما صدت، حتى تحول نجماً يتعقبها في السماء". كل هذا يؤكد هوية هذا المكان، وهذا ما تتحدث عنه "ناديا" مع "آدم": "لماذا لم يحافظوا عليها - تقصد الهوية -؟ هذا دليل على حضارات سابقة". وتفسر هذا بزحف الأغراب على المكان حتى أصبح بلا ذاكرة.

تنوع الأساليب

تقوم حوارية الرواية على تعدد الأساليب، إذ تجمع بين الأسلوب الشاعري والبحث العلمي والدعاء والحكمة والاسترجاع وتضمين الشعر وآيات من القرآن الكريم. ومن شواهد الأسلوب الشاعري قول "ناديا": "أنا الكائن الحي الذي يتجه إلى النور، ماذا أفعل إن كان نفقي بلا نور؟". فالشاهد يقوم على رمزية النور والنفق. أما أسلوب البحث العلمي فيتضح في قولها: "في تقرير صادر منذ سبعة وعشرين عاماً، يذكر أن أسماك الحراسين وجدت داخل إحدى العيون". وأسلوب الدعاء في قول: "دوب سار ماخ": "بنورك المضيء يتبعك البحر/ إلهي أتيتك راجياً العبور". وأسلوب الحكمة حين يقول الأب المعلم: "تآخوا، كل منكم عليه التمسك بشقيق يشد من أزره". وهناك أسلوب الاسترجاع الغالب على سرد "ناديا". ومن تضمين الشعر هذا البيت: "ما بال عينك لا تجود بمائها/ والنفس قد طويت على غمائها". وتضمين آيات القرآن مثل "فلينظر الإنسان ممَّ خلق، خلق من ماء دافق". هذه الرواية تقدم عالماً غرائبياً، لكن هذه الغرائبية كانت من آلاف السنين واقعاً يعيشه الناس.

https://www.independentarabia.com/node/594006/%D8%AB%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%A9/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B3%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%A1%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AA%D8%AE%D9%8A%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D8%AD%D8%B1

The Forgotten Between Two Waters

: A Novel of Imagined Life in a Maritime World

Leila Al-Mutawa recounts a wondrous history between water and desert

Although the Bahraini writer Leila Al-Mutawa is a feminist activist and a defender of women’s rights, her novel The Forgotten Between Two Waters reaches well beyond the bounds of “women’s issues.” In part, it surveys—through a myth-tinted lens—the history of the inhabitants of an island, while also offering pointed social reflections on the condition of women as embodied by several female figures.

In this new novel (Dar Rashm), Al-Mutawa attends closely to the meaning of the “two waters” of the title: the water of the sea and the water of the springs that rise within it. Hence the name “Bahrain,” given to this geographical region. Water is the central signifier. The author, as she describes herself, is “a daughter of water,” a daughter of an island for whom the sea forms part of identity. She does not exaggerate when she places over one sub-heading: “From water we are—and to water we shall return,” a cadence that echoes the Qur’anic verse, “We made from water every living thing.” All this signals the singularity of this local place, past and present. Chief among its marvels is the presence of fresh-water springs in the depths of a salty sea, and the novel’s weaving-in of the region’s most resonant myths: the Epic of Gilgamesh—who journeyed here in search of the herb of immortality—and the Phoenician legend of the woman whose infants never lived, freed from the curse only by treading the blood of a nobleman. This, in the novel, is what happens with “Salīmah,” who steps in the blood of “Ṭarafa” after his combat with the governor’s envoy.

Ṭarafa ibn al-ʿAbd

Though Ṭarafa’s life—despite its tragic end—was passed over briefly in older sources, it has been treated often in Bahrain, most notably in the life written by the poet Qassim Haddad. A line in which Ṭarafa alludes to women “who never rear a living child” sparked the author’s idea for this book. She invented the figure of “Salīmah,” who seized her chance and trod Ṭarafa’s blood. Thus the fire of vengeance flared within his sister “al-Kharnāq.” What Salīmah did did not please her husband “Ṣafwān,” who warned her that al-Kharnāq “eats only camel flesh; she feeds on her rancour and on the memory of those who wronged her.” Yet al-Kharnāq did not resort to force or open confrontation; she chose guile. She lay in wait for the governor to pass and recited verses praising the beauty of a shapely, hazel-eyed woman, ripe and much desired. The governor ignored it at first; when the scene recurred, he asked those around him about this beauty. None could lead him to her. Desire took hold of him; he summoned al-Kharnāq and asked, and she, with a sly smile, replied: “She is Salīmah, the wife of Ṣafwān.” The governor bid his servant request that Ṣafwān honour him—with Salīmah’s body. The couple escaped this snare only by sending another beautiful woman to the governor in Salīmah’s stead. When al-Kharnāq learned of it, she again caught the governor’s ear and called him a dupe. Once he confirmed the deceit, he ordered Ṣafwān killed and crucified. Salīmah, pregnant, fled to the far shore—astonishingly giving birth in the sea, then carrying the newborn to land.

A Chorus of Voices

Although the novel is told chiefly in the voice of the contemporary narrator “Nadia,” it still makes room for a polyphony of perspectives, moving between third-person narration and the first-person voice in the chapter “What Happened to Nadia,” where she says: “I spin in circles. The sun above me burns; it hurts my eyes. This is the place that Salīmah crossed, as the account relates. But where is the sea? Where is the blue of the water, its changing hues?” These closing questions mark a transformation of place—whether wrought by the sea itself or by human hands.

The book abounds in oppositions: between a past reaching back millennia—figured by “Ṭarafa,” “Salīmah,” her mother “Buthayna,” her husband “Ṣafwān,” and “al-Kharnāq”—and a present embodied by “Nadia,” her grandmother “Najwa,” and her teacher “Adam.” In truth, the pairing is complementary: the present summons the past not only to affirm identity but to refract it upon the contemporary moment. Another, more polarised opposition is the struggle between sea and desert, water and land; and a complementary counter-pairing sets myth against reality, and sweetness against salinity—fresh springs against the sea. “These springs,” Adam says, “were among the reasons for the pearl’s purity—fresh water in the midst of the salt sea. Our forebears, the divers, would replenish their water from them during pearling voyages.” Here the pair is complementary. Not so with water and land: most springs, we are told, “have dried up because of land-reclamation and construction, the building of artificial islands and the widening of the shore.” Hence deception: a mirage of water in the desert, and a mirage of land at sea.

To this is added the drama of the duel between Ṭarafa and the mercenary sent by the governor, who cried out as he circled so the gathered crowd would hear: “Choose the manner of your death—for kill you I shall.” Ṭarafa spurned him with his famed pride: he knew he sprang from a noble clan whose forelocks are never shorn, whose women are never reviled, whose men bare their chests to death, bow to no king, and fear no hireling. And yet he died a cruel death.

There also runs through the book a persistent mythic cast of mind: myth as a way of life for these people, a companion to their very being, a guide to their steps. Salīmah feels the clutch of a hand upon her skin and finds there the print of a small palm: the hand of her daughter “Umaymah,” the sacrificial victim whose body “dissolved with the flow of water years ago.” Before Salīmah crosses the sea, they warn her not to reach for any fruit, “for the sea will know—and will demand it—and the boat will capsize,” a reminder of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit and being cast out of the garden. It also recalls Lot’s wife, turned to a pillar of salt for looking back: Ṣafwān hears “the voices of the women in pain as they walked away from the sacred ground—‘Resist; do not look back.’” There is, too, the sacrifice of firstborn daughters—said to have been practised in ancient Egypt—where nobles of every tribe brought their girls to the well; when the high priestess proclaimed the water, they heard its gurgle and cried out in joy. In parallel stands life born from death: what Salīmah does with Ṭarafa to be granted a child. As for the nature-myths: it is told that “al-Dabbarān” was a poor man who “loved the ravishing Thurayya; he gave her his flock, but she refused him. He followed her, however she turned away—until he became a star that chases her across the sky.” All this affirms the identity of this place, the very point Nadia makes to Adam: “Why did they not preserve it—this identity? It is proof of earlier civilisations.” Her answer is the steady encroachment of outsiders until the place was left without a memory.

A Weave of Styles

The novel’s dialogic texture draws on multiple registers: the poetic and the scientific report, the supplication, the aphorism, the flashback, with verses of poetry and quotations from the Qur’an folded in. A sample of the poetic note is Nadia’s line: “I am the living creature moving toward the light—what am I to do if my tunnel has no light?” The research register appears in: “A report issued twenty-seven years ago mentions that harāsīn fish were found within one of the springs.” The voice of prayer is heard in “Dubsar Makh”: “By Thy shining light the sea follows Thee; / My God, I come to Thee, begging passage.” As for the aphoristic tone, the teacher-father says: “Be brethren—each of you must hold fast to a brother who will strengthen him.” Flashback dominates Nadia’s narration. Among the quoted lines of verse: “What ails your eye, that it will not yield its water / While the soul lies folded in its gloom?” And from the Qur’an: “So let man consider from what he was created—created from a gushing fluid.”

This is a novel that presents a world of marvels; yet what now strikes us as marvellous was, thousands of years ago, the texture of life itself.

تعليقات

إرسال تعليق